Medway Creek

...a trail during January Thaw

Though the midwinter upsurge in temperature appears consistent enough, the phenomenon is not recognized as real – it is what meteorologists call a “singularity”. A singularity is an annual weather episode, usually an anomalous departure that reoccurs at roughly the same time every year in a majority of years.

It also notes that Toronto only once in 150 Januaries has had no thaw period. This year, Toronto has had far little snow, and London did receive a dose of snow earlier during New Years Eve when the temperatures dropped to below -10C. During the period of January Thaw in the third week, the temperatures rose to about 6C, the snow created pools of water and mud, and the sky shone brightly! It was a break I was looking for during midwinter, to get out of the classroom in the basement and explore the woods.

With such a “singularity” blessing, I wandered to the Medway Creek that runs in front of my house. It’s a blissful place – a nigh fifteen feet from the road alongside. I wrote about Medway Creek during fall, which can be read HERE.

With such a “singularity” blessing, I wandered to the Medway Creek that runs in front of my house. It’s a blissful place – a nigh fifteen feet from the road alongside. I wrote about Medway Creek during fall, which can be read HERE.

So exploring Medway Creek wasn’t new to me, but surprisingly, it was – very new, very different. The sound of water gushing beneath a crust of ice, the dripping of snow off the bare branches, little plants lying dead in the graveyard of snow – it was a surreal. There wasn’t enough activity of the animals, although their presence was felt everywhere. There were Black-capped Chickadees high in the trees, dancing around merrily – always hiding from me. I haven’t managed a single photograph of these birds yet! And there were other signs of the teeming life during winter – that of White-tailed Deer, Cotton-tail Rabbits and raccoons. None were sighted, unfortunately.

So exploring Medway Creek wasn’t new to me, but surprisingly, it was – very new, very different. The sound of water gushing beneath a crust of ice, the dripping of snow off the bare branches, little plants lying dead in the graveyard of snow – it was a surreal. There wasn’t enough activity of the animals, although their presence was felt everywhere. There were Black-capped Chickadees high in the trees, dancing around merrily – always hiding from me. I haven’t managed a single photograph of these birds yet! And there were other signs of the teeming life during winter – that of White-tailed Deer, Cotton-tail Rabbits and raccoons. None were sighted, unfortunately.

This task is easy but the identification is far from easy. So I took help from Walter Muma, owner of Ontario Wild Flowers website

And took photographs of what I thought was interesting.

After exploring some of these dried plants, how much ever boring or exciting you might think it is, I noticed these three mushrooms. It’s not that I saw them for the first time – I have been seeing them since I got here in September. I haven’t identified them yet, never photographed ‘em before, but I felt this was the time to capture them. The three ‘shrooms on a bent tree-trunk, with a backdrop of snow laden riverbank was a beautiful sight! These are probably related to the Bracket Fungi, which, when they die, do not disintegrate easily but leave behind a hard, woody structure. This could be a reason why the three fungi are still intact on the tree.

After exploring some of these dried plants, how much ever boring or exciting you might think it is, I noticed these three mushrooms. It’s not that I saw them for the first time – I have been seeing them since I got here in September. I haven’t identified them yet, never photographed ‘em before, but I felt this was the time to capture them. The three ‘shrooms on a bent tree-trunk, with a backdrop of snow laden riverbank was a beautiful sight! These are probably related to the Bracket Fungi, which, when they die, do not disintegrate easily but leave behind a hard, woody structure. This could be a reason why the three fungi are still intact on the tree.

While walking along the creek, as I photographed the scenery around, I was stuck with a thought of how evolution works. It is one of the processes that cannot be predicted in time. It is either slow, or fast. It can either lead to a successful species, or extinction (survival of the fittest). It is a pure, strong natural force driving life from its very beginning. It will only lead to further evolution; hence it will never stop on its own. Until we interfere. Human interference is termed anthropogenic, something man-made, “artificial”, something that we devised and not nature. But we forget we’re a product of nature – of this evolution. Like non-related species lead to evolution of some other species, we’re but a part of this relationship – where we, the non-related species let other species evolve.

It is in our perception, however, the way we see such evolution – as either constructive or destructive. First thing that comes to my mind when I see us as a reason for evolution is the invasion of exotic species. Be it by an accident – such as introduction of many plants and animals in other environments – such as Garlic Mustard, Crazy Yellow Ants, and rodents on Australian islands and so on. Or be it on purpose, such as introducing exotic ornamental trees such as Delonix regia, or Acacia pycnantha for a greener tree cover and the Giant African Snail in India, or the introduction of biological pest controls such as Cane Toad in Australia, and of domestic animals in the wild. All of this took place in not more than a hundred years – too short to see any signs of evolution, but the effects are already seen.

In case of Medway Creek – or any in the Thames River Watershed, the invasive species such as Zebra Mussel have posed a threat to the native diversity of mussels – this might contribute to evolution or extinction of some, it’s a part of the survival of the fittest. There’s Buckthorn, an invasive plant species posing a threat to the native flora in Thames valley. It is a game of waiting for a thousand or even million years to see the actual effects. But in case of invasive species, it’s always the opposite of evolution. Thus, in order to minimize the extinction rate – which is faster than the rate of evolution, we must act as a responsible part of this biodiversity by eradicating the invasive species (we caused the invasion, we must sort it out, too!).

In case of Medway Creek – or any in the Thames River Watershed, the invasive species such as Zebra Mussel have posed a threat to the native diversity of mussels – this might contribute to evolution or extinction of some, it’s a part of the survival of the fittest. There’s Buckthorn, an invasive plant species posing a threat to the native flora in Thames valley. It is a game of waiting for a thousand or even million years to see the actual effects. But in case of invasive species, it’s always the opposite of evolution. Thus, in order to minimize the extinction rate – which is faster than the rate of evolution, we must act as a responsible part of this biodiversity by eradicating the invasive species (we caused the invasion, we must sort it out, too!).

“Whose woods are these I think I know

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.”

- Robert Frost, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.”

- Robert Frost, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening

Medway Creek - as seen from a bridge

I was growing impatient for the arrival of spring. This was a month ago, in January – a month considered to be the bleakest of all. Spring is yet far from now. I continued my daily chores of going to school every day, missing the song of the birds and merry squirrels that would scour on the ground. The snow filled the landscape, so much so that I hardly ever saw anything that’s green and not white. The weather was ever in transit – once it was cloudy and windy and sometimes bright and calm. I welcomed the sun every time I saw it thawing the icy mounds.

Then came a week in January, of something unexplained and loved by all – January Thaw. January Thaw is a climatic phenomenon of unseasonably warm temperatures that tend to occur at about the same time every year (usually in the second or third week of January).

The Canadian Encyclopedia writes,

Though the midwinter upsurge in temperature appears consistent enough, the phenomenon is not recognized as real – it is what meteorologists call a “singularity”. A singularity is an annual weather episode, usually an anomalous departure that reoccurs at roughly the same time every year in a majority of years.

It also notes that Toronto only once in 150 Januaries has had no thaw period. This year, Toronto has had far little snow, and London did receive a dose of snow earlier during New Years Eve when the temperatures dropped to below -10C. During the period of January Thaw in the third week, the temperatures rose to about 6C, the snow created pools of water and mud, and the sky shone brightly! It was a break I was looking for during midwinter, to get out of the classroom in the basement and explore the woods.

Footprints of a White-tailed Deer

Medway Creek is one of the tributaries of Thames River, and one of the much polluted ones at that. It is unfortunate that the tree cover is thinning in much urbanized parts and the increasing road runoffs adding to the pollution. It is a source of water for the wildlife that lingers around, and a prime habitat for aquatic animals. The UTRCA graded it at D for its forest cover and a C for its water quality. NOT good.

Many footprints on the ice over the creek

After walking around the creek, seeing no animals around – I considered photographing dried plants.

, one of the best online sources for identification of all kinds of flora of Ontario!

As I walked onto the snow laden ground, searching for signs of life, I recorded a video, which can be seen below,

And took photographs of what I thought was interesting.

Daucus carota

One such dried plant that grabbed my attention was Wild Carrots – Daucus carota. It is a common plant throughout the landscape in Southern Ontario which is edible. The flowers when dry come close together and form an interesting design.

Staphylea sp. (?)

Another plant that I noticed was identified as a Bladdernut – Staphylea sp. The identification is uncertain. It was dead and dripping with melting snow. The flowers are ornamental and possess a bladder-like fruit – hence the name.

Alliaria petiolata

Then it was Garlic Mustard – Alliaria petiolata, a pretty flowering plant of Mustard family. However, as other plants, only the pods were seen attached to it. It is an edible plant. Unfortunately, it was introduced in North America as a culinary herb and has found its way into the woods where it thrives amongst other native plants. It has a status of “invasive species” and is of much concern throughout Thames River Watershed.

Dipsacus sp.

Teasel – Dipsacus sp. was also common throughout the banks of Medway Creek. These too are considered ornamental. The seeds are a good food source during winter for birds and hence grown in natural reserves to attract them.

Viburnum sp.

Another pretty – but dried – plant was Highbush Cranberry – Viburnum sp. This shrub is native to North America and is commonly seen all over. The fruits are sour and rich in Vitamin C.

After exploring some of these dried plants, how much ever boring or exciting you might think it is, I noticed these three mushrooms. It’s not that I saw them for the first time – I have been seeing them since I got here in September. I haven’t identified them yet, never photographed ‘em before, but I felt this was the time to capture them. The three ‘shrooms on a bent tree-trunk, with a backdrop of snow laden riverbank was a beautiful sight! These are probably related to the Bracket Fungi, which, when they die, do not disintegrate easily but leave behind a hard, woody structure. This could be a reason why the three fungi are still intact on the tree.

After exploring some of these dried plants, how much ever boring or exciting you might think it is, I noticed these three mushrooms. It’s not that I saw them for the first time – I have been seeing them since I got here in September. I haven’t identified them yet, never photographed ‘em before, but I felt this was the time to capture them. The three ‘shrooms on a bent tree-trunk, with a backdrop of snow laden riverbank was a beautiful sight! These are probably related to the Bracket Fungi, which, when they die, do not disintegrate easily but leave behind a hard, woody structure. This could be a reason why the three fungi are still intact on the tree.While walking along the creek, as I photographed the scenery around, I was stuck with a thought of how evolution works. It is one of the processes that cannot be predicted in time. It is either slow, or fast. It can either lead to a successful species, or extinction (survival of the fittest). It is a pure, strong natural force driving life from its very beginning. It will only lead to further evolution; hence it will never stop on its own. Until we interfere. Human interference is termed anthropogenic, something man-made, “artificial”, something that we devised and not nature. But we forget we’re a product of nature – of this evolution. Like non-related species lead to evolution of some other species, we’re but a part of this relationship – where we, the non-related species let other species evolve.

It is in our perception, however, the way we see such evolution – as either constructive or destructive. First thing that comes to my mind when I see us as a reason for evolution is the invasion of exotic species. Be it by an accident – such as introduction of many plants and animals in other environments – such as Garlic Mustard, Crazy Yellow Ants, and rodents on Australian islands and so on. Or be it on purpose, such as introducing exotic ornamental trees such as Delonix regia, or Acacia pycnantha for a greener tree cover and the Giant African Snail in India, or the introduction of biological pest controls such as Cane Toad in Australia, and of domestic animals in the wild. All of this took place in not more than a hundred years – too short to see any signs of evolution, but the effects are already seen.

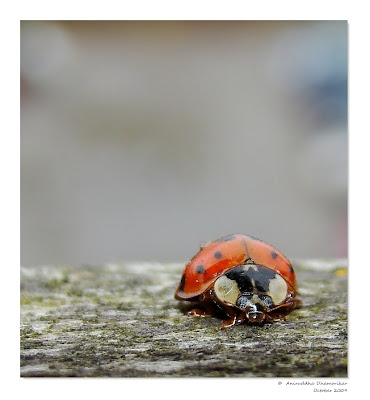

Harmonia axyridis

All invasive species are pests. Whether accidentally or purposely introduced. Take the example of the Asian Lady beetle – Harmonia axyridis (which can be read HERE). These fellows should be hibernating for winter, but several individuals were out as the temperatures rose during the thaw period. H. axyridis were introduced to protect crops from aphids but ended up being a pest themselves – posing a threat to the native ladybird beetles. Now we see more of H. axyridis than any native beetles in London. All of this also brings to my mind the “survival of the fittest”. Why is it that on an average, the invasive species tend to be more successful in a foreign habitat than the native ones? There are several reasons, such as possessing toxic chemicals, being disease resistant, so on. This is because of the way in which the respective invasive and the native species evolved.

Footprint of a White-tailed Deer on snow

Most of the barriers that existed before, such as mountains, rivers and oceans are no more barriers. Humans have a vast network of transportation, thus accelerating invasion far and wide. Only extensive monitoring can reduce this, and more efforts be made in curing the already persistent invasive species.

Wonderful photography and interesting blog. Way to go!

ReplyDelete